Organizing and structuring unit tests

June 11th, 2020

Here's some notes on how I organize my unit tests. It's about how I structure, organize and name my projects, my classes and the tests themselves. These are things that I found out through trial-and-error. This article will be focused on .NET and Visual Studio, but many of the practices can be applied to other languages, frameworks and IDEs.

Project structure

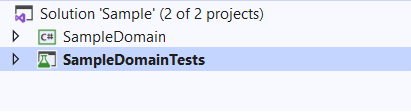

I create a unit test project for each project in my solution that I want to test. I give the unit test project the same name as its "sister" project, but suffix it with "Tests". Like this:

I often see a unit test project suffixed with ".Tests" (note the dot), but I'm not a fan of that. It makes it look as if the unit test project resides within the project I am testing, being a sub namespace of it, and that very explicitly is not the case. The unit test is its own project and as such deserves its own namespace.

The reason I create a separate unit test project, instead of making it part of the project I am testing, is that it forces me to use the public API of the project I am testing. I can't "accidentally" test through methods that are declared as having internal scope. This way I have to really consider the design of the API when writing tests for it.

Class structure

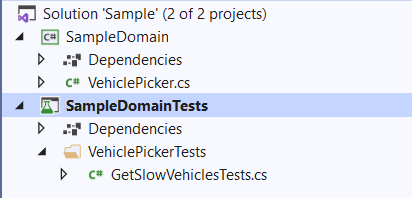

Within the unit test project, I create a separate folder for each class I am about to test. The name of the folder is the name of the class I am testing, suffixed with "Tests". In that folder, I create a class for each public method I want to test. The name of the class is the name of the method I am testing suffixed with "Tests". Like this:

As you can see from the folder name and class name, here I am testing the method "GetSlowVehicles" of the class "VehiclePicker".

It may feel kind of cumbersome to suffix everything with "Tests". I experimented with only suffixing the unit test class with "Tests", but then I ran into problems with namespaces in the test project conflicting with namespaces in its sister project. In this case I prefer clarity over succinctness.

The reason for having a folder per class under test, and a class file for each method under test, is that it is common to have between a handful and a dozen of test cases per method under test. Organizing the tests in this way keeps the size of each test class small and manageable.

Naming unit tests

Here is an example of one of the unit tests:

[TestMethod]

public void SingleSlowVehicleAndSingleFastVehicle()

{

var sut = new VehiclePicker();

var aSlowVehicle = "moped";

var aFastVehicle = "rocket";

var vehicles = new List { aSlowVehicle, aFastVehicle };

var slowVehicles = sut.GetSlowVehicles(vehicles);

Assert.AreEqual(aSlowVehicle, slowVehicles.Single());

}

I've experimented a lot with naming the test cases. One thing I see often is that test case names follow a Give-When-Then format, or some variant of it. For example: "GivenSingleSlowVehicleAndSingleFastVehicle_WhenGettingSlowVehicles_ThenOnlySlowVehicleShouldBeReturned". The Given-When-Then format makes sense when specifying a BDD-style acceptance tests, because then the Given-When-Then specification *is* the test. However, here I think the name, while absolutely clear, includes redundancy, and can be shorter.

The filename of our test class already tells us what method I am testing. It will be repeated for each test in this class, so it will be obvious and I can leave that out of the test name. Also the Then part can be figured out easily by looking at the Assert part of the test. If it isn't easy to figure out what the expected result of the test should be, then that is a sign the test needs to be simpler: perhaps it is testing multiple things instead of a single thing. That leaves just the Given-part of the test for the name, and that is often sufficient. It's a good exercise to put "The one with the..." in front of each test name, like an episode of "Friends", and see if it makes sense. If it does, then it is a good name.

Initialization

I have put the initialization of the object (vehiclePicker) in the test case itself, because in this case it is a single line of simply newing up the class. If the construction of the object is more complicated, perhaps because it includes initializing one or more mock-objects, then I prefer to do the construction in the Initialization step of the test class. Like this:

private VehiclePicker vehiclePicker;

private Mock<ISomething> mockSomething;

[TestInitialize]

public void Initialize()

{

mockSomething = new Mock<ISomething>();

vehiclePicker = new VehiclePicker(mockSomething.Object);

}

Some people don't like this, because they prefer to have all relevant test code, including construction code, within the test method. This keeps everything within eyesight. It is a valid argument, but when having small, cohesive test classes, and using the Initialize step consistently, I think it ultimately improves readability of the unit tests.

Some people prefer the Builder pattern for constructing more complex classes, such as data objects with default test values. I have used that as well, but I find that tucking away test data in another class often makes it harder to understand what is going on in a test method than declaring it at the top of the test class in an Initialize step. Your mileage may vary and I encourage you to try the various options and form your own opinion on this.

I named the thing we are testing "sut". I now prefer this over naming it, for example, "vehiclePicker". Generally, it is a good idea to name things after the role they play in the specific piece of code, rather than after their type. Naming the thing we are tesing "sut" also makes the tests more resilient against refactoring. If we ever decide to rename the VehiclePicker class to something else, we wouldn't have to rename it in the tests.

Assert

Let's look at that assert statement again:

... Assert.AreEqual(aSlowVehicle, slowVehicles.Single()); ...

I like to keep my tests focused on testing a single thing, and as a result most of my Asserts are of the "AreEqual" kind. I could have also asserted that "slowVehicles" wasn't null. I could have also asserted that "slowVehicles" contains exactly one item. But those checks are already covered by the using ".Single()" method. Adding extra checks would only confuse what the test is about.

I sometimes hear the argument that those extra checsk would make the cause of a failure more clear. But if I let this test fail by unexpectedly returning multiple items, I get the message: "Sequence contains more than one element", which seems plenty clear to me. So, just test what you need to test.

Conclusion

In this article I have shown you some practices I use to organize and structure my unit tests. I hope you have found it valuable, and that you use it to improve your own unit tests.